September 11, 2008

Scientists have developed nanometer-sized ‘cargo ships’ that can sail throughout the body via the bloodstream without immediate detection from the body’s immune radar system and ferry their cargo of anti-cancer drugs and markers into tumors that might otherwise go untreated or undetected.

In a forthcoming issue of the Germany-based chemistry journal Angewandte Chemie, scientists at UC San Diego, UC Santa Barbara and MIT report that their nano-cargo-ship system integrates therapeutic and diagnostic functions into a single device that avoids rapid removal by the body’s natural immune system. Their paper is now accessible in an early online version here.

“The idea involves encapsulating imaging agents and drugs into a protective ‘mother ship’ that evades the natural processes that normally would remove these payloads if they were unprotected,” said Michael Sailor, a professor of chemistry and biochemistry at UCSD who headed the team of chemists, biologists and engineers that turned the fanciful concept into reality. “These mother ships are only 50 nanometers in diameter, or 1,000 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair, and are equipped with an array of molecules on their surfaces that enable them to find and penetrate tumor cells in the body.”

These microscopic cargo ships could one day provide the means to more effectively deliver toxic anti-cancer drugs to tumors in high concentrations without negatively impacting other parts of the body.

“Many drugs look promising in the laboratory, but fail in humans because they do not reach the diseased tissue in time or at concentrations high enough to be effective,” said Sangeeta Bhatia, a physician, bioengineer and professor of Health Sciences and Technology at MIT who played a key role in the development. “These drugs don’t have the capability to avoid the body’s natural defenses or to discriminate their intended targets from healthy tissues. In addition, we lack the tools to detect diseases such as cancer at the earliest stages of development, when therapies can be most effective.”

The researchers designed the hull of the ships to evade detection by constructing them of specially modified lipids--a primary component of the surface of natural cells. The lipids were modified in such a way as to enable them to circulate in the bloodstream for many hours before being eliminated. This was demonstrated by the researchers in a series of experiments with mice.

The researchers also designed the material of the hull to be strong enough to prevent accidental release of its cargo while circulating through the bloodstream. Tethered to the surface of the hull is a protein called F3, a molecule that sticks to cancer cells. Prepared in the laboratory of Erkki Ruoslahti, a cell biologist and professor at the Burnham Institute for Medical Research at UC Santa Barbara, F3 was engineered to specifically home in on tumor cell surfaces and then transport itself into their nuclei.

|

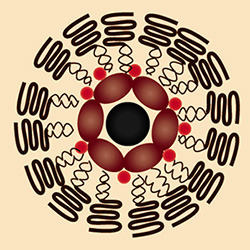

| A vial of anti-cancer nano ships glows red under a black light. The particles glow red because they contain fluorescent "quantum dot" nanoparticles. Credit: Luo Gu, UCSD |

“We are now constructing the next generation of smart tumor-targeting nanodevices,” said Ruoslahti. “We hope that these devices will improve the diagnostic imaging of cancer and allow pinpoint targeting of treatments into cancerous tumors.”

The researchers loaded their ships with three payloads before injecting them in the mice. Two types of nanoparticles, superparamagnetic iron oxide and fluorescent quantum dots, were placed in the ship’s cargo hold, along with the anti-cancer drug doxorubicin. The iron oxide nanoparticles allow the ships to show up in a Magnetic Resonance Imaging, or MRI, scan, while the quantum dots can be seen with another type of imaging tool, a fluorescence scanner.

“The fluorescence image provides higher resolution than MRI,” said Sailor. “One can imagine a surgeon identifying the specific location of a tumor in the body before surgery with an MRI scan, then using fluorescence imaging to find and remove all parts of the tumor during the operation.”

The team found to its surprise in its experiments that a single mother-ship can carry multiple iron oxide nanoparticles, which increases their brightness in the MRI image.

“The ability of these nanostructures to carry more than one superparamagnetic nanoparticle makes them easier to see by MRI, which should translate to earlier detection of smaller tumors,” said Sailor. “The fact that the ships can carry very dissimilar payloads—a magnetic nanoparticle, a fluorescent quantum dot, and a small molecule drug—was a real surprise.”

The researchers noted that the construction of so-called “hybrid nanosystems” that contain multiple different types of nanoparticles is being explored by several other research groups. While hybrids have been used for various laboratory applications outside of living systems, said Sailor, there are limited studies done in vivo, or within live organisms, particularly for cancer imaging and therapy.

“That’s because of the poor stability and short circulation times within the blood generally observed for these more complicated nanostructures,” he added. As a result, the latest study is unique in one important way.

“This study provides the first example of a single nanomaterial used for simultaneous drug delivery and multimode imaging of diseased tissue in a live animal,” said Ji-Ho Park, a graduate student in Sailor’s laboratory who was part of the team. Geoffrey von Maltzahn, a graduate student working in Bhatia’s laboratory, was also involved in the project, which was financed by a grant from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

The nano mother ships look individually like a chocolate-covered nut cluster, in which a biocompatible lipid forms the chocolate shell and magnetic nanoparticles, quantum dots and the drug doxorubicin are the nuts. They sail through the bloodstream in groups that, under the electron microscope, look like small, broken strands of pearls.

The researchers are now working on developing ways to chemically treat the exteriors of the nano ships with specific chemical “zip codes,” that will allow them to be delivered to specific tumors, organs and other sites in the body.

Media Contact: Kim McDonald, 858-534-7572

Comment: Michael Sailor, 858-534-8188